|

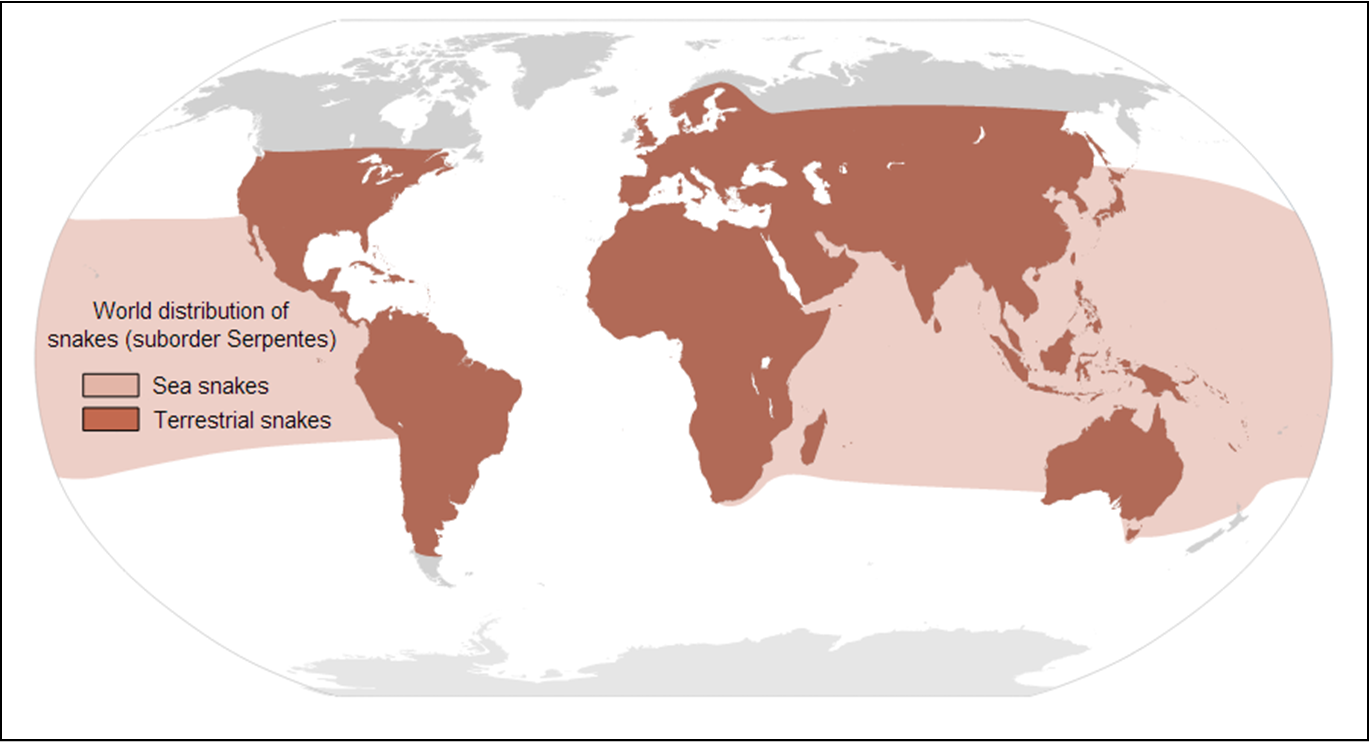

| Map of snake envenomings per year, from Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix) bite a few hundred people a year in my home state of North Carolina, more than in any other state. Fatalities are exceedingly uncommon. |

|

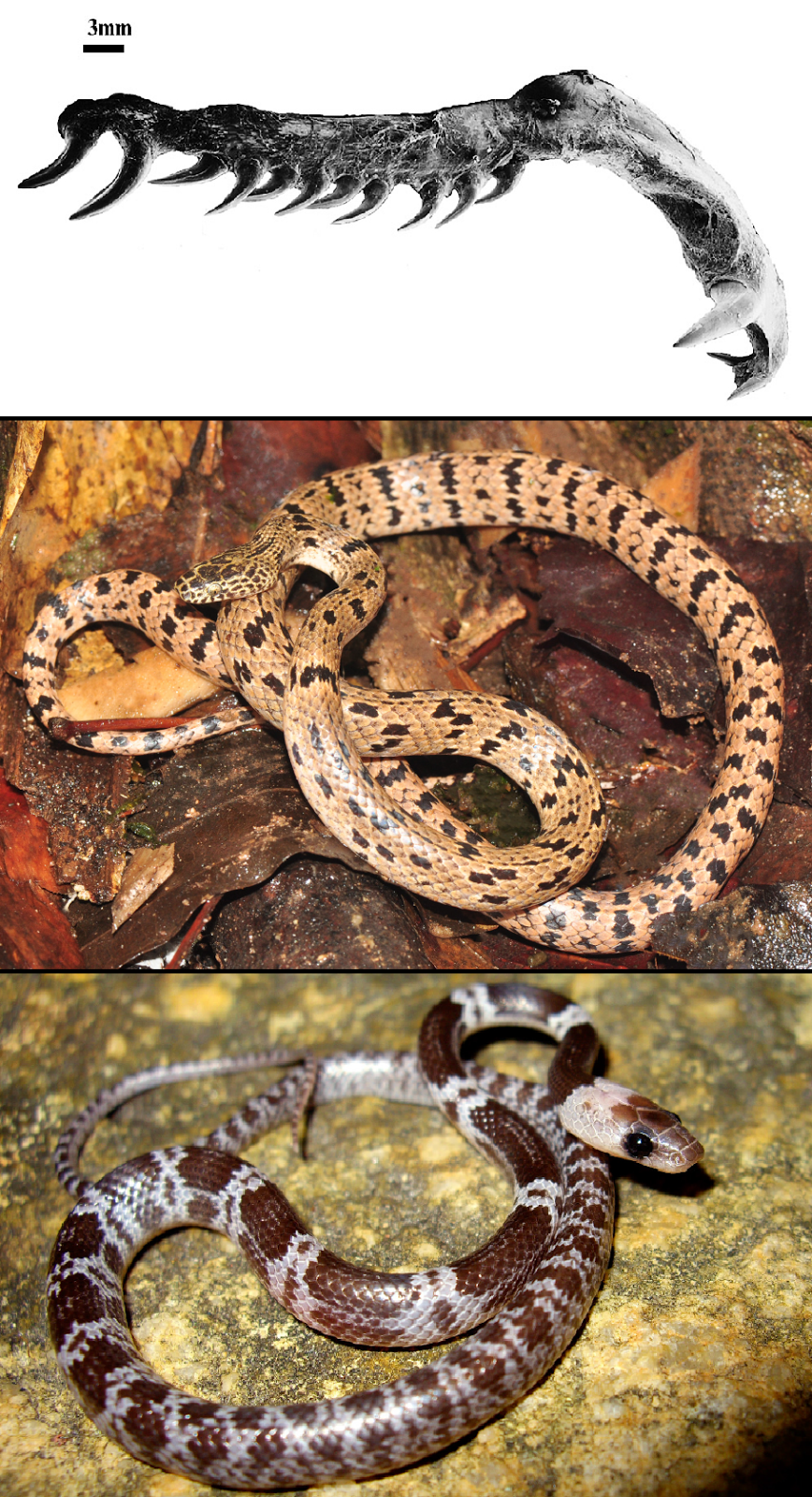

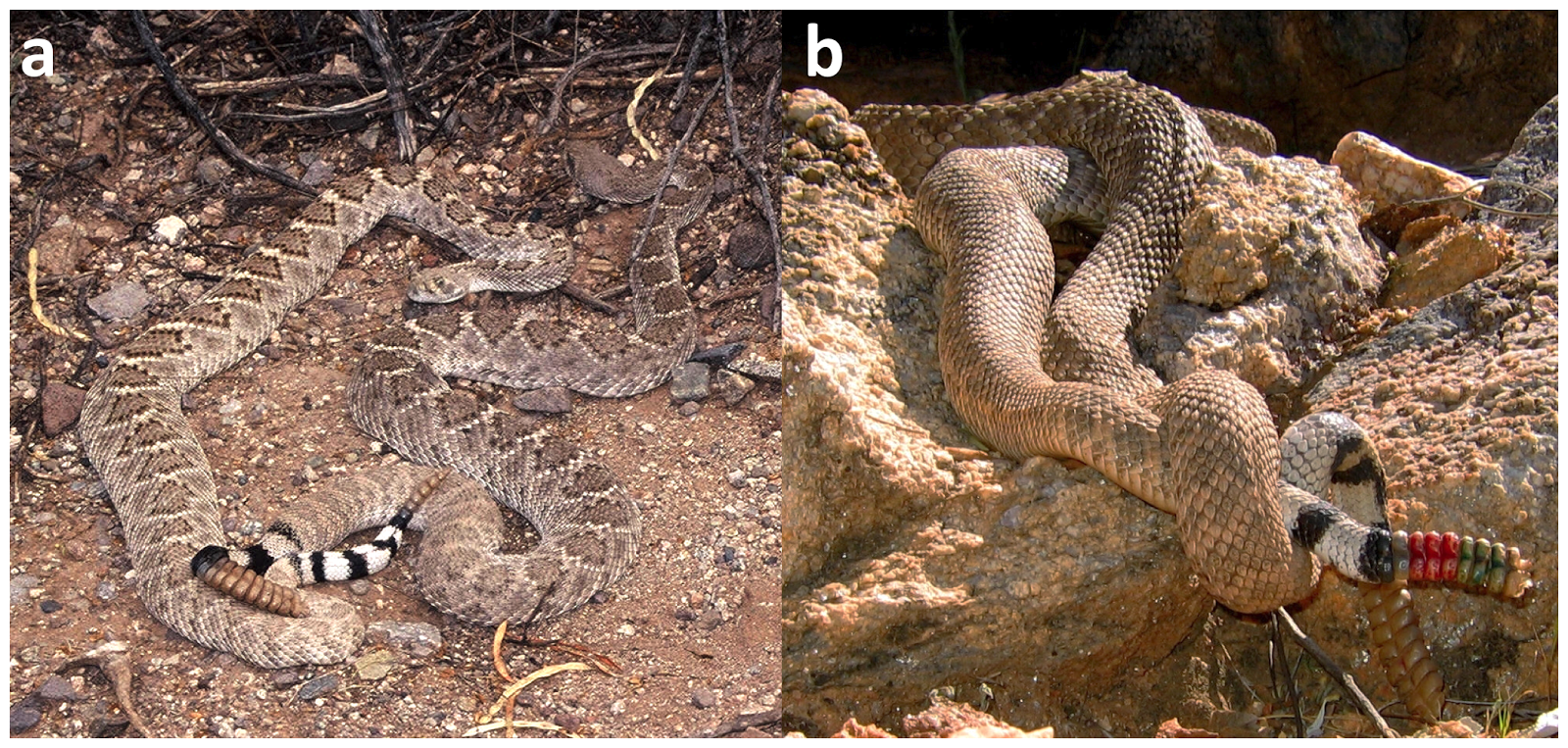

| Western Diamondback Rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox) are large and widespread in the southwestern USA. A recent study showed rattlesnake size to be among the most important factors determining bite severity, with the largest snakes causing the most serious bites. |

|

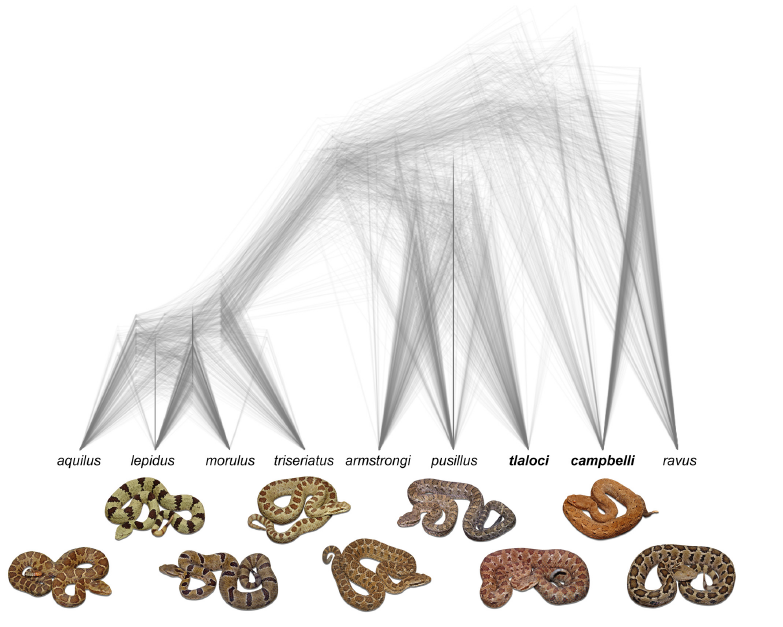

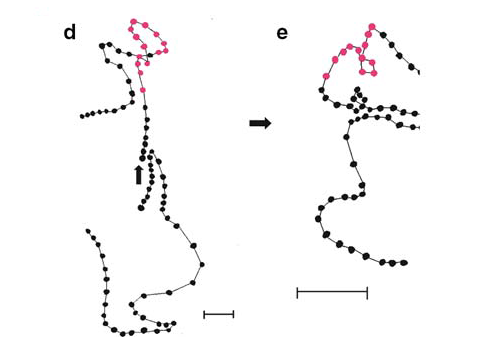

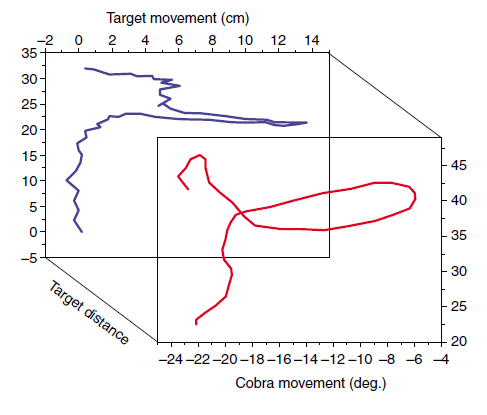

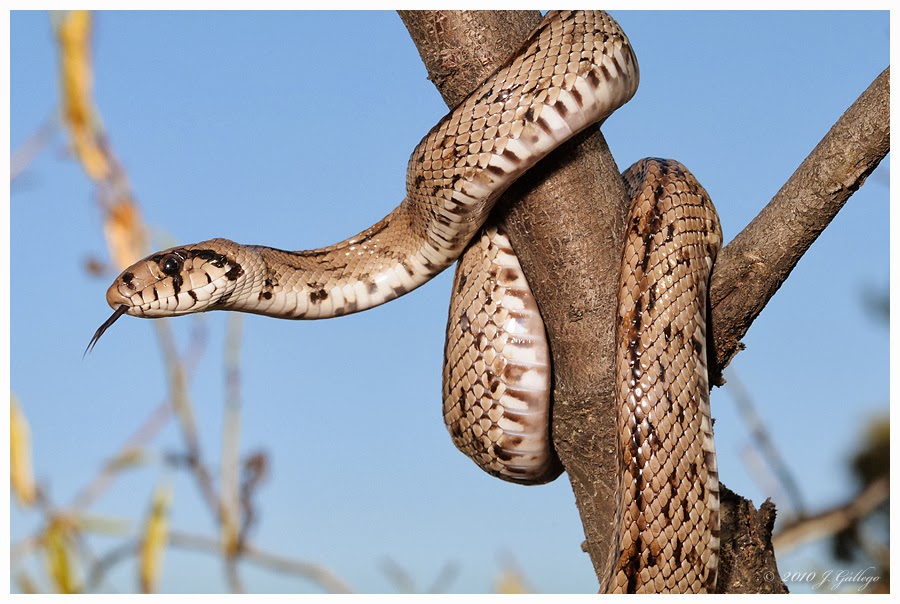

| Figure from Gibbons & Dorcas (2002) |

|

| Black Mambas (Dendroaspis polylepis) are among Africa's most dangerous snakes, but they still kill fewer people than hippos or mosquitos |

|

| CroFab antivenom used to treat most snakebites in the USA |

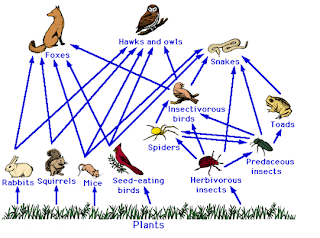

Yet more than 1 in 20 people in the USA have a pathological fear of snakes, as defined by criteria including uncontrollable, greater than justified, and significantly interferes with a person’s routine, occupational or academic functioning, or social activities or relationships. Leading to situations like this recent news story and this bizarre interaction between a man, a gun, and a snake. Risk perception is influenced by many things, including the rarity of the event, how much control people think they have, the adverseness of the outcomes, and whether the risk is voluntarily or not. For example, people in the United States underestimate the risks associated with having a handgun at home by 100-fold, and overestimate the risks of living close to a nuclear reactor by 10-fold. Ironically, evidence suggests that two of these things (how much control you have and how voluntary the risk is) are actually quite high for snakebite, despite popular perception that is it low.

fady to kill any snake. In contrast, in Australia people seem to have a relatively high level of respect for snakes and don't seem to mess with them solely out of machismo the way they do in the USA. Venomous snakebites are relatively rare, which is remarkable considering that the majority of snakes in Australia are venomous. I heard a story recently about a newly-hired Australian CEO of an American mining company. When the new boss asked about the snake policy, the employees jokingly replied that it was "a No. 2 shovel". The Australian CEO was not amused, because at his previous company Down Under routinely relocated much more dangerous snakes at their job sites. He instituted a company-wide training program to teach safe venomous snake practices. These classes are also available to the general public in some areas, especially in southern Africa.

1 Venomous snakes that are striking at their prey practically always inject venom, and in fact can precisely meter their venom so that they inject exactly the right amount needed to kill each particular prey item, based on its mass. Fortunately for humans, there are no venomous snakes large enough to consider us prey.↩

2 Although global snakebite statistics frequently list 0 fatalities out of 200-300 snakebites for Canada, this seems not to be quite accurate. In Ontario, at least two people have been killed by Timber Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus), a soldier who was bitten at the battle of Lundy's Lane near Niagara Falls in 1814, and an American Indian chief prior to 1850. Two or three people have been killed by bites from Massasaugas (Sistrurus catenatus) in Ontario, all before 1962, and between 0 and 10 people were bitten annually from 1971-2007, mostly men aged 10-29. In 1981, a man who was "quite intoxicated" was killed by a bite from a Northern Pacific Rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus) on the Nk’meep reserve near the town of Osoyoos in British Columbia's Okanagan Valley. He was the first person to be bitten by a native venomous snake in BC in over 50 years. The only other Canadian provinces that are home to venomous snakes are the Prairie Provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, where no recorded deaths have occurred from Prairie Rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis) bites. So we can conclude that native snakebites in modern Canada are even more infrequent than but follow the same basic pattern as those in the USA.↩

3 In the US, relative to dying from heart disease (1 in 5), cancer (1 in 7), in a motor vehicle accident (1 in 80), in a fall (1 in 185), from a gunshot (1 in 300), by drowning (1 in 1100), by choking (1 in 4400), from drinking too much alcohol (1 in 10,900), by a sting from a wasp, bee, or hornet (1 in 63,000), from being struck by lightning (1 in 80,000), from a dog bite (1 in 120,000), or in an earthquake (1 in 150,000), you are very unlikely to be killed by a snake (1 in 480,000). The only less-likely causes of death are being trapped in a low-oxygen environment (1 in 548,000), being killed by ignition or melting of nightwear (1 in 767,000), and being bitten by a spider (1 in 960,000). These odds are for your entire lifetime; your annual chance of being killed by a venomous snake is more like 1 in 50 million. Worldwide, they're more like 1 in 200,000, which is a lot higher but still pretty low overall.↩

(click here for a full list of references pertaining to snakebite)

Gibbons, J. W. and M. E. Dorcas. 2002. Defensive behavior of Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) toward humans. Copeia 2002:195-198 <link>

Glaudas, X., T. M. Farrell, and P. G. May. 2005. The defensive behavior of free–ranging pygmy rattlesnakes (Sistrurus miliarius). Copeia 2005:196-200 <link>

Janes Jr, D. N., S. P. Bush, and G. R. Kolluru. 2010. Large snake size suggests increased snakebite severity in patients bitten by rattlesnakes in southern California. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 21:120-126 <link>

Juckett, G. and J. G. Hancox. 2002. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. America Family Physician 65:1367-1375 <link>

Parrish, H. M. 1966. Incidence of treated snakebites in the United States. Public Health Reports 81:269-276 <link>

Swaroop, S. and B. Grab. 1954. Snakebite Mortality in the World. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 10:35-76 <link>

Tierney, K. J. and M. K. Connolly. 2013. A review of the evidence for a biological basis for snake fears in humans. The Psychological Record 63:919-928 <link>

Walker, J. P. and R. L. Morrison. 2011. Current management of copperhead snakebite. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 212:470-474 <link>

.jpg)

.jpg)