This article will soon be available in Spanish.

Do snakes sleep? Do they dream? These may seem like obvious questions, especially since almost every species of mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, fish, and invertebrate studied has been found to exhibit some kind of resting phase. But sleep is hard to study in snakes, at least in part because they seem never to close their eyes. Consequently, there is shockingly little research on sleep in snakes. A Google Scholar search for the terms "snake+sleep" returns papers about venomous snakebites to sleeping victims, sleepwalkers dreaming about snakes, and papers by Stanford geophysicist Norman H. Sleep on the geology of the Snake River in Idaho. But, despite the dearth of research, I promise this post won't be too much of a snooze...

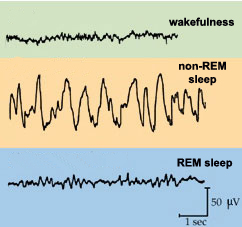

|

| Human EEG "brainwaves" |

|

| Lizards wearing EEG-recording equipment while awake and asleep From Flanigan 1973 |

|

| Waking (top) and sleeping (bottom) python EEG and EMG waves. From Peyrethon & Dusan-Peyrethon 1969 |

Snakes do have circadian rhythms, and many snakes are active only at particular times of day. Racers (Coluber), hog-nosed snakes (Heterodon), patch-nosed snakes (Salvadora), and sipos (Chironius) are strictly diurnal, whereas aptly-named nightsnakes (Hypsiglena), broad-headed snakes (Hoplocephalus), and kraits (Bungarus) are strictly nocturnal. But many snakes do not fit nicely into these categories. Good examples include ratsnakes (Pantherophis) and many vipers, but many other snakes may be active at any time of the day or night, depending on the time of year, so it's hard to predict when or for how long they might be expected to sleep. You often observe snakes exhibiting sleep-like behavior, sitting in one spot for hours, days, or even weeks at a time, like the Puff Adder (Bitis arietans) in the video at left. But the thing is, that snake is actually foraging. A viper might sit motionless for many days, such a long time that if a mammal exhibited that same behavior, we might think it was sick or dead! But in fact this is how many snakes forage for prey, hyper-alert to their immediate surroundings, ready to ambush, strike, and envenomate small animals that stray too close. Do they sleep when they are waiting, or are they awake the entire time? Radio-telemetry studies of bushmasters (Lachesis muta) in the wild suggest that they might have strict cycles of attentiveness, "awesomely alert during darkness and almost as if drugged by day", with relatively abrupt transitions each way. On the other hand, many marine mammals and migratory birds do not seem to sleep for long periods of time without suffering any obvious consequences. When engaged in constant activity, these animals close one eye and sleep one half of their brain at a time. Other animals, including perhaps some lizards, sleep one hemisphere at a time in contexts of high predation risk. Might snakes that use sit-and-wait foraging strategies do something similar?

| I photographed this Sonoran Lyresnake (Trimorphodon lambda) during the day, but it was found at night. Their skinny slit-like pupils enhance their night vision, making distant objects sharper by increasing the depth of field, like using a small aperture on a camera lens. If lyresnakes sleep, it's probably during the day. |

So here's what we know: snakes probably do sleep, perhaps most of the time, but we don't really know when, for how long, how deeply, or whether or not they have paradoxical sleep, including dreaming. Sleep patterns are probably quite diverse across the >3500 species, of which only one has been examined. Many snakes do yawn, but this has been interpreted either as a means to gather chemical cues or to reposition musculoskeletal elements, in contrast with the hypothesized functions of yawning in humans (possibly regulating brain temperature, causing increases in blood pressure, blood oxygen, and/or heart rate in order to improve motor function and alertness, or as a social cue). Sleep is such a basic element of human biology, so if you ask me, the subject of sleep in snakes, and broader questions about the diversity, evolution, and function of sleep across the animal kingdom, should be keeping researchers awake at night.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Kendal Morris for suggesting this question, and to Harry Greene, David Cundall, and Gordon Burghardt for sharing their observations.

REFERENCES

Ayala-Guerrero, F., & Huitrón-Reséndiz, S. 1991. Sleep patterns in the lizard Ctenosaura pectinata. Physiology & Behavior 49:1305-1307 <link>

Bauchot, R. 1984. The phylogeny of sleep in vertebrates [birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish]. Annee Biologique (France) 23:367-392 <link>

Brischoux, F., Pizzatto, L., & Shine, R. 2010. Insights into the adaptive significance of vertical pupil shape in snakes. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23:1878-1885 <link>

Campbell, S. S., & Tobler, I. 1984. Animal sleep: a review of sleep duration across phylogeny. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 8:269-300 <link>

De Vera, L., González, J., & Rial, R. V. 1994. Reptilian waking EEG: slow waves, spindles and evoked potentials. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 90:298-303 <link>

Flanigan, W. F. 1973. Sleep and wakefulness in iguanid lizards, Ctenosaura pectinata and Iguana iguana. Brain, Behavior, and Evolution 8:417-436 <link>

Hartse, K.M. and A. Rechtschaffen. 1974. Effect of atropine sulfate on the sleep-related EEG spike activity of the tortoise, Geochelone carbonaria. Brain, Behavior, and Evolution 9:81-94 <link>

Peyrethon, J., & Dusan-Peyrethon, D. 1969. Etude polygraphique du cycle veille-sommeil chez trois genres de reptiles. CR Soc Biol (Paris) 163:181-186 <not available online>

Rattenborg, N. C. 2006. Do birds sleep in flight? Naturwissenschaften 93: 413-425 <link>

Roe, J. H., Hopkins, W. A., Snodgrass, J. W., & Congdon, J. D. 2004. The influence of circadian rhythms on pre-and post-prandial metabolism in the snake Lamprophis fuliginosus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 139:159-168 <link>

Siegel, J. M. 2008. Do all animals sleep? Trends in Neurosciences 31: 208-213 <link>

Siegel, J. M., Manger, P. R., Nienhuis, R., Fahringer, H. M., Shalita, T., & Pettigrew, J. D. 1999. Sleep in the platypus. Neuroscience 91: 391-400 <link>

Tauber, E.S., J. Rojas-Ramirez, and R. Hernandez-Peon. 1968. Electrophysiological and behavioral correlates of wakefulness and sleep in the lizard (Ctenosaura pectinata). Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 24:424–443 <link>

Bauchot, R. 1984. The phylogeny of sleep in vertebrates [birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish]. Annee Biologique (France) 23:367-392 <link>

Brischoux, F., Pizzatto, L., & Shine, R. 2010. Insights into the adaptive significance of vertical pupil shape in snakes. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23:1878-1885 <link>

Campbell, S. S., & Tobler, I. 1984. Animal sleep: a review of sleep duration across phylogeny. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 8:269-300 <link>

De Vera, L., González, J., & Rial, R. V. 1994. Reptilian waking EEG: slow waves, spindles and evoked potentials. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 90:298-303 <link>

Flanigan, W. F. 1973. Sleep and wakefulness in iguanid lizards, Ctenosaura pectinata and Iguana iguana. Brain, Behavior, and Evolution 8:417-436 <link>

Greene, H. W., & Santana, M. 1983. Field studies of hunting behavior by bushmasters. Estudios de campo del comportamiento de caza por parte de las cascabelas mudas. American Zoologist 23:897 <link>.

Hartse, K.M. and A. Rechtschaffen. 1974. Effect of atropine sulfate on the sleep-related EEG spike activity of the tortoise, Geochelone carbonaria. Brain, Behavior, and Evolution 9:81-94 <link>

Libourel, P. A., & Herrel, A. 2015. Sleep in amphibians and reptiles: a review and a preliminary analysis of evolutionary patterns. Biological Reviews <link>

Peyrethon, J., & Dusan-Peyrethon, D. 1969. Etude polygraphique du cycle veille-sommeil chez trois genres de reptiles. CR Soc Biol (Paris) 163:181-186 <not available online>

Rattenborg, N. C. 2006. Do birds sleep in flight? Naturwissenschaften 93: 413-425 <link>

Roe, J. H., Hopkins, W. A., Snodgrass, J. W., & Congdon, J. D. 2004. The influence of circadian rhythms on pre-and post-prandial metabolism in the snake Lamprophis fuliginosus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 139:159-168 <link>

Siegel, J. M. 2008. Do all animals sleep? Trends in Neurosciences 31: 208-213 <link>

Siegel, J. M., Manger, P. R., Nienhuis, R., Fahringer, H. M., Shalita, T., & Pettigrew, J. D. 1999. Sleep in the platypus. Neuroscience 91: 391-400 <link>

Tauber, E.S., J. Rojas-Ramirez, and R. Hernandez-Peon. 1968. Electrophysiological and behavioral correlates of wakefulness and sleep in the lizard (Ctenosaura pectinata). Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 24:424–443 <link>

Life is Short, but Snakes are Long by Andrew M. Durso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.