|

| Spitting cobras have been known for centuries, as you can see from this report published in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society in 19001 |

|

| A clever comic from birdandmoon highlighting the fact that king cobras are not true cobras |

|

| Mozambique Spitting Cobra (Naja mossambica) |

| ||

|

| ||

| ||

|

|

| Sumatran Spitting Cobra (Naja sumatrana) |

|

| Rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus) |

|

| The largest Giant Spitting Cobras (Naja ashei) can top 9 feet. This species was described in 2007. From Wüster & Broadley 2007 |

Nearly 100 years after Barbour, we have just as little direct evidence—published field observations of spitting cobras interacting with their non-human predators are non-existent. The main reason we now think that the evolutionary cause of these adaptations isn't so simple is that spitting is too old. Molecular dating methods suggest that African spitting cobras evolved about 15 million years ago, whereas the spread of open grasslands and their characteristic megafauna (elephants, etc.) didn't happen until about 5 million years ago. Asian spitting cobras don't inhabit open grasslands, so this hypothesis seems unlikely to explain their evolution either. African spitting cobras are eaten by birds and other snakes, against which spitting venom would be a relatively ineffective weapon, and in captive experiments cobras do not spit at mounted bird specimens. Given what we know about face targeting, it's possible that spitting may represent a defense that is specifically adapted for use against primates [Edit: Harry Greene hinted at this idea in his recent book,Tracks and Shadows]. Barbour's comment that "...[venom spitting] must antedate man's coming, for contact between man and the snakes can hardly be conceived as sufficiently frequent to account for the modification" may be technically correct, but the evolution of spitting cobras coincides roughly with the evolution of apes in Asia and Africa, which (as we all know) are diurnal primates with forward-facing eyes, some of which are omnivorous and many of which (ourselves included) habitually kill snakes either for food or in defense. Could it be that spitting cobras evolved their venom spitting capacity to deal with threats from our own ancestors? Only further research into the co-evolution of apes and snakes can tell us. Perhaps this is why, although certain toads, salamanders, insects, and scorpions can also eject their toxin defensively, spitting cobras are by far the longest- and best-known organisms to do so. Clearly, much remains to learn about them and their fascinating habits.

1 The cobra in this account was undoubtedly Naja mandalayensis, which was described by Joe Slowinski & Wolfgang Wüster 100 years later. Before 2000, no spitting cobras were known from Burma. Cobra specimens with fangs highly modified for spitting from northeastern India may represent a seventh species of undescribed Asian spitting cobra.↩

2 This number includes species of cobras formerly placed in the genera Boulengerina and Paranaja, both of which have been synonymized with Naja in the last 15 years. In part, the reason for this change is that, when scientists realized that some species of Naja were more closely related to Boulengerina and Paranaja than they were to other Naja (i.e., that Naja was paraphyletic), they were reluctant to split up the genus Naja because they didn't want to change the name of medically-important snakes and create potential confusion. However, a few sources use Afronaja and other other subgenera as full genera anyway.↩

3 The fang sheath is soft tissue that completely surrounds the fang at rest, including at the top, which keeps the venom from dribbling out. In other venomous snakes, physical contact with a target is required for displacement of the fang sheath and release of venom, but spitting cobras have co-opted the movements normally used for jaw-walking over a prey item (the ‘pterygoid walk’) to free their fangs for spitting in the absence of any external physical contact. This has been termed the "buccal buckle" (pronounced "buckle buckle") by the research group of Bruce Young, of Kirksville College, which has studied several aspects of the functional morphology of spitting in cobras.↩

4 Naja philippinensis is the only spitting cobra species with pronounced sexual dimorphism in discharge orifice size—females have longer orifices less well-adapted for spitting, whereas males have small round orifices. The evolutionary causes and consequences of this dimorphism are not understood.↩

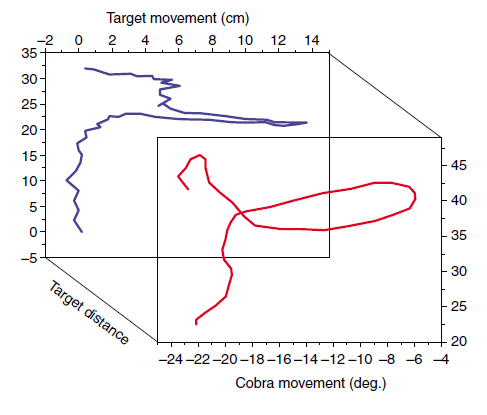

Berthé, R., S. de Pury, H. Bleckmann, and G. Westhoff. 2009. Spitting cobras adjust their venom distribution to target distance. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 195:753–757 <link>

Berthé, R.A., G. Westhoff, and H. Bleckmann. 2013. Potential targets aimed at by spitting cobras when deterring predators from attacking. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 199:335-340 <link>

Bogert, C.M. 1943. Dentitional phenomena in cobras and other elapids, with notes on adaptive modifications of fangs. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 81:285-360 <link>

Cascardi, J., B.A. Young, H.D. Husic, and J. Sherma. 1999. Protein variation in the venom spat by the red spitting cobra, Naja pallida (Reptilia: Serpentes). Toxicon 37:1271-1279 <link>

Goring Jones, M.D. 1900. Can a cobra eject its poison? Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 8:376 <link>

Hayes, W., S. Herbert, J. Harrison, and K. Wiley. 2008. Spitting versus biting: differential venom gland contraction regulates venom expenditure in the Black-Necked Spitting Cobra, Naja nigricollis nigricollis. Journal of Herpetology 42:453-460 <link>

Keogh, J.S. 1998. Molecular phylogeny of elapid snakes and a consideration of their biogeographic history. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 63:177-203 <link>

Petras, D., L. Sanz, Á. Segura, M. Herrera, M. Villalta, D. Solano, M. Vargas, G. León, D.A. Warrell, and R.D.G. Theakston. 2011. Snake venomics of African spitting cobras: toxin composition and assessment of congeneric cross-reactivity of the pan-African EchiTAb-Plus-ICP antivenom by antivenomics and neutralization approaches. Journal of Proteome Research 10:1266-1280 <link>

Rasmussen, S., B. Young, and H. Krimm. 1995. On the ‘spitting’ behaviour in cobras (Serpentes: Elapidae). Journal of Zoology 237:27-35 <link>

Slowinski, J.B. and W. Wüster. 2000. A new cobra (Elapidae: Naja) from Myanmar (Burma). Herpetologica 2000:257-270 <link>

Szyndlar, Z. and J.C. Rage. 1990. West Palearctic cobras of the genus Naja (Serpentes: Elapidae): interrelationships among extinct and extant species. Amphibia-Reptilia 11:385–400 <link>

Triep, M., D. Hess, H. Chaves, C. Brücker, A. Balmert, G. Westhoff, and H. Bleckmann. 2013. 3D Flow in the Venom Channel of a Spitting Cobra: Do the Ridges in the Fangs Act as Fluid Guide Vanes? PLoS ONE 8:e61548 <link>

Wallach, V., W. Wüster, and D.G. Broadley. 2009. In praise of subgenera: taxonomic status of cobras of the genus Naja Laurenti (Serpentes: Elapidae). Zootaxa 2236:26-36 <link>

Westhoff, G., K. Tzschätzsch, and H. Bleckmann. 2005. The spitting behavior of two species of spitting cobras. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 191:873-881 <link>

Wüster, W. and D.G. Broadley. 2007. Get an eyeful of this: a new species of giant spitting cobra from eastern and north-eastern Africa (Squamata: Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja). Zootaxa 1532:51-68 <link>

Wüster, W., S. Crookes, I. Ineich, Y. Mané, C.E. Pook, J.F. Trape, and D.G. Broadley. 2007. The phylogeny of cobras inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences: Evolution of venom spitting and the phylogeography of the African spitting cobras (Serpentes: Elapidae: Naja nigricollis complex). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 45:437-453 <link>

Wüster, W. and R.S. Thorpe. 1992. Dentitional phenomena in cobras revisited: spitting and fang structure in the Asiatic species of Naja (Serpentes: Elapidae). Herpetologica:424-434 <link>

Young, B.A., M. Boetig, and G. Westhoff. 2009. Spitting behaviour of hatchling red spitting cobras (Naja pallida). The Herpetological Journal 19:185-191 <link>

Young, B.A., K. Dunlap, K. Koenig, and M. Singer. 2004. The buccal buckle: the functional morphology of venom spitting in cobras. Journal of Experimental Biology 207:3483-3494 <link>